The day the Circus came to Town - Pete Norman

October 2010

The day the circus came to town the monsoon came with it. Well, maybe not quite the inundation that sweeps down the Earth’s greatest mountain range to devastate a continent, but even for Blackpool this rain was quite impressive: the traffic in Queens Promenade, obscured by the heavy grey curtain, was reduced to mere insubstantial phantoms hissing and splashing their way past her window; and the sea . . . well, the sea just wasn’t there any more.

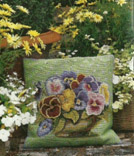

Gladys Hardwick waited patiently while the nurse threaded her needle; her arthritis was now sufficiently advanced that she was unable to perform even that simple task herself. But sheer determination drove her onwards; she slipped her tongue between her teeth and, ignoring the spikes of pain that surged through her misshapen knuckles, eased the needle through the fabric, pulling the deep purple thread up through the heart of a pink and white pansy. She had been embroidering beautiful cushions for over fifty years now and they would drag her out of this place feet first before she would ever give up her precious sewing.

‘Don’t suppose they’ll be able to do it in this rain.’ she said, ‘Shame – I was quite looking forward to seeing it.’

Sandra stared out through the misted glass, her fingers absently ruffling through Gladys’ thinning, snow white hair, ‘Well, the forecast did say it would only be showers, perhaps it will clear up for the afternoon.’

‘They were going to have elephants; I haven’t seen elephants since . . .’ her eyebrows furrowed as she tried to remember when she had actually last seen a real elephant, in the flesh, so to speak. It had to have been London Zoo, but she had only been a little girl then – more years ago than she cared to remember now.

‘I’m sure the elephants will need a walk after they have been cramped up in their cages all that time.’ Sandra said, hopefully, ‘We’ll get our parade, Gladys, you wait and see.’

‘Nurse!’ a plaintive but insistent call cut across the Vera Lynn muzak, which played constantly, monotonously, to sooth the more troublesome ones; ‘Nurse!’

Sandra groaned, ‘It’s Walter . . . weak bladder Walter.’ she laughed, ‘Give me a call when you need another colour,

my lovely.’ and she hurried off in a vain attempt to prevent disaster.

The rain did indeed clear up in the afternoon – it wasn’t exactly sunny, but it held off just long enough for a few of them to be wheeled out onto the front path to watch as three sad looking elephants trooped slowly past, coaxed along by an elderly man: a leopard skin stretched tight over the expanding contours of his stomach; his hair, so falsely black, hinting at a virility he had long since surrendered. Flanking them, a handful of garishly dressed clowns danced their way along the promenade, pressing colourful flyers into the hands of small excited children and squirting water into giggling faces.

But Gladys wasn’t watching the clowns, because, coming up behind them, were two women and three men sheathed in brightly coloured skin tight lycra costumes, so tight they left very little to the imagination – the Flying Bugrovis. The girls looked so young, skeletally thin but quite elegant with their gracefully exaggerated movements. The first two men were a little older than the girls, but still thin bordering on the skinny.

‘I prefer mine with a bit more meat on the bone!’ Sandra laughed, but Gladys’ attention was fixed on the third man, who was quite a bit older than the other two.

She froze.

Fifty long years dropped from her shoulders in an instant and she cried out, ‘Michael . . . Michael . . . is that you?’ but the troop was already disappearing behind the tall laurel hedge that fronted the Cherry Tree Guest House next door.

Sandra took her trembling hand, ‘Oh, Gladys! What are you doing?’ she pleaded.

Gladys looked up at her, her eyes moist, ‘It’s my son, Michael . . . I know it is this time, Sandra – I do, I really do.’

Sandra shook her head sadly, ‘No, my lovely. We’ve been through all this before, haven’t we . . . several times.’ she smiled warmly, ‘That is not your son, Sweetheart, you just get a little confused, that’s all.’

Trying to de-fuse the situation, she pointed to the two tired old horses which brought up the rear and laughed,

‘Now, the Recorder said they were Arab stallions, but those horses have never been any closer to Arabia than

Wimbledon Common.’ But Gladys was in a world of her own, staring blankly at the impenetrable screen of the hedge,

‘It was Michael, I know it was.’

Thursday afternoon was truly another day; the sun shone from a clear blue sky and Gladys felt an almost child-like exuberance as she was lifted down from the minibus. The circus was doing a special for Seniors and Gordon had finally bowed to the intense pressure and allowed five of them to go along.

The Big Top, though dwarfed by the vastness of Stanley Park which surrounded it, was still impressively huge and one by one they were wheeled through the wide opening and up to a privileged position right up against the ringside barrier.

The smell of sawdust and damp canvas, mingling with a vague hint of animal, was almost overwhelming, creating a unique environment and whetting the appetite for the fun to follow. Gladys took in the tiers of benches rising upward to the heavens; the trapeze ropes dangling precariously from the very top ridge; the twin curtains on the other side of the arena, through which she caught occasional glimpses of brightly painted props and busy preparations being made.

Slowly the seats filled up around them until the tent was almost three quarters full; mostly Baby Boomers, Gladys noted - truly a force to be reckoned with when offers were around!

Then, suddenly, to a fanfare, the twin curtains parted and the Ringmaster strode in, resplendent in his black trousers and waistcoat, with a long ruby red tail-coat jacket. He pirouetted in the centre of the ring, doffing his black top hat at each section of the audience in turn. Then, he introduced the performers: first the clowns, tumbling around, leaping up onto the ringside barrier, teasing the children . . . and some of the older ladies too, much to their delight; a steady ripple of laughter and applause followed them around.

As the clowns disappeared through the curtains again, the Flying Bugrovis exploded past them, arms thrust out, huge smiles lighting up their faces. As they paraded around the edge of the ring, Gladys focussed on the Great Bugrovi as he approached. Now that he was no more than ten feet in front of her, she was certain: those piercing blue eyes, that unkempt mop of curly blond hair, that impish grin – there was no doubt in her mind – no doubt at all.

She rose unsteadily, her arms outstretched, ‘Michael?’ but her weak legs gave way and she collapsed heavily beside her chair. The Great Bugrovi stopped, the overt self confidence on his face melting into confusion and concern. He leapt the barrier and crouched beside her, ‘Madame,’ he said, his voice thickly accented, ‘Are you alright?’

Gordon, meanwhile, had pushed his way through the concerned crowd and took the Great Bugrovi by the arm, lifting him to his feet. ‘Gordon Sanderson.’ he offered his hand, ‘She’s one of mine, I am afraid. Look, I’m so sorry about this . . .’ his stage whisper carried clearly through the hushed air, ‘It seems Gladys had a child taken away from her when she was a teenager and she’s always thinking she sees him in a crowd.’ he smiled sadly, ‘Though how she expects to recognise him again when he was only new-born when she saw him last, I’ll never know.’

Gladys’ eyes hardened and she raised herself up on one elbow, ‘But I got me a good enough look at the father though, didn’t I!’ she snarled.

Sandra put a protective arm around her shoulder and shushed her, ‘But, Gladys, how can he be your son, he’s not even English.

The First Aider set his bag down beside her, ‘That’s right, my love, The Great Bugrovi is from Russia – St Petersburg, isn’t it, Vladimir?’ he winked up at his colleague and reached for her pulse.

Gladys moaned and sank back down. Sandra said, ‘You see, Gladys, St Petersburg is a very long way from Ramsbottom, isn’t it?’

The Great Bugrovi’s face froze.

Sandra said, ‘You did say it was Ramsbottom, didn’t you? . . . small town near Bury, you said, wasn’t it, Gladys?’

Vladimir Bugrovi (a.k.a. Michael Arkwright) dropped down beside her again; all trace of Eastern European gone, he said in broad Mancunian, ‘I was born in Fairfield General . . . I never knew my mother . . .’